The concept of setting the bar higher is widely accepted and celebrated, and rightly so. We often push ourselves and our businesses to new heights by setting new goals and targets. However, even though sometimes the distance between goal envisioned and goal achieved is merely an extra effort away, we often don’t attain the desired heights.

Apart from obvious external impeding factors (market acceptance, competition, lack of resources) and probable internal ones (lack of competence, courage, insight, discipline), there is one particular factor we don’t consider as much as we could be. Often we no longer believe in attainability of our own goals due to conclusions based on the wrong measurements of previously failed attempts.

When we attempt something challenging, and fail, several things happen:

- we tend to loose motivation;

- we begin to doubt our ability to overcome the challenge;

- we are more likely to distrust the judgment of people who put us up to the challenge.

It goes something like this: “I’ve tried and failed many times, so it must prove that this is unattainable for me, and whoever thinks otherwise is wrong.”

But the reality might turn out to be quite different. Here is a short story to illustrate this.

More similar attempts prove us more wrong

A few years before COVID-19 outbreak my son was attending basketball practice sessions organized by Steady Buckets in NYC. I chaperoned him to these 2-hour workouts once a week. And while he was sweating away on the court I had little else to do other than chat with other parents, read a book or watch how kids learn basketball basics.

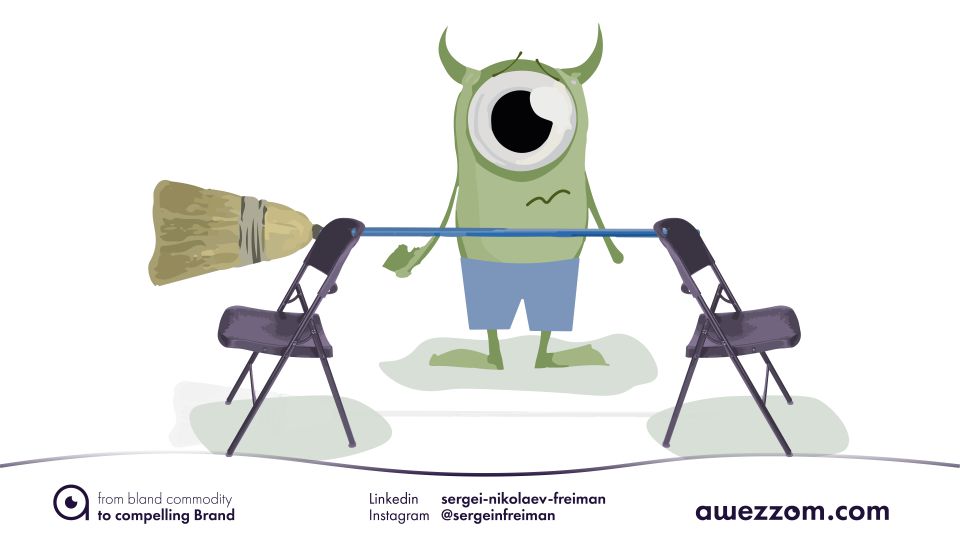

One of those days when kids were grouped into different activities I noticed a bunch of teenage girls practicing jumps. One of the coaches told them to assemble a makeshift barrier to jump over. So, the girls took two folding chairs, positioned them opposite each other at a distance, and put a regular broom on top of the chairs. Apparently, this wasn’t the first time they did this.

Girls took turns doing the jumps. No matter how hard they tried to jump over this bar they would either collide with or tag the handle of the broom and watch it fall down. So after several attempts they decided to lower the bar. But folding chairs don’t offer a lot of bar-lowering options: you can either place the broom on the seat or on the top of the back of the chair. One of the girls put the broom across the seats.

With bar being much lower all of the girls were able to jump over it without any real effort. They celebrated the first jumps dully and then just stood there by the makeshift challenge awaiting further instructions. Jumping over the bar at this height wasn’t fun anymore as everyone already did it more than once without much of an effort.

The coach eventually noticed this, and told the girls to raise the bar and continue jumping. The girls had to put the broom back at the initial top level. But of course none of them were able to jump over the bar this time either.

I happened to sit nearby on one of the lower benches which allowed me to notice something the girls themselves weren’t able to pick up. My eyesight was level with the makeshift bar. So when either of the three girls attempted another jump I could very well see what was happening.

In order to jump over an obstacle like that two conditions have to be met: the pelvis and the feet of the jumper have to be above the bar at a certain point in time and space. During the jump the body travels along an arc. Thus at a particular moment the body reaches the arc’s peak and then travels back down.

As an outside observer I’ve noticed something the girls haven’t figured out yet. Every girl was jumping above the bar: both pelvis and feet. But two factors prevented them from successfully jumping over. First, they either initiated their jumps further from the obstacle or, second, they were too swift to lower their feet to safeguard themselves from falling.

So, the first part of the problem was technical (objective) — distance. The second part was emotional (subjective) — fear. It wasn’t that the girls weren’t capable of jumping over the bar or that they didn’t try hard enough — they didn’t know they could actually do it and all the (their) evidence suggested they couldn’t. Because if they knew they could, they would have inevitably asked a follow-up question — how.

First few failed attempts planted the seeds of doubt: “I can’t do it, none of my friends can do it — it must be unattainable for either of us.” The more attempts they made the less convinced of possible success they got.

I kept observing the jumps to make sure the girls were consistently capable and consistently failing. I also took note of one girl who appeared to be trying the hardest. So, when everyone had their three-minute break I approached that girl and told her about my observations.

As you might’ve have guessed, after the break, on the very next attempt the girl I spoke to approached the challenge, hesitated a brief few moments and jumped over the bar — no problem. She did it!

Not a single external factor had changed — just her approach. All I did was lay out the objective facts and provide encouragement. She did everything herself. She moved closer to the broom, pushed the ground away, pulled her knees closer toward the chest and held her legs a split-second longer during the jump.

She then shared her own newly acquired knowledge and experience with her friends. A few minutes in and both her friends were able to overcome the challenge as well.

Resemblance with a Professional services firm

This story shares a common thread with a typical professional services firm. At first, top management sets the bar high. People try hard and fail. Everyone gets discouraged and people trust less in their own abilities and even less in their management’s ability to set attainable targets.

Often, to counter this, management puts the bar much lower, and soon employees get bored and frustrated with not having enough challenging work. Morale declines and financial performance follows suit.

Just like athletes, firms care about performance. The problem with low financial performance of a typical firm isn’t that people aren’t capable of reaching the specified targets; they just don’t know how. And here is why:

- people have subjective biases and assumptions, e.g., they’ve already failed and now don’t believe their goals are attainable;

- they often don’t know which measurements are relevant to their particular situations, and so they measure the wrong things which feed wrong assumptions;

- there is little to no encouragement to continue pursuit, because management is none the wiser or, alas, doesn’t care.

What can you do about this at your firm?

Key takeaways for professional services firms

Here are a few takeaways from this story:

- After a few failed attempts firms tend to lower the bar. The work gets done. But the trade-off is that when it isn’t challenging anymore, it isn’t fun. So, people either stop doing what’s no longer fun or slowly flush their morale down the drain. This of course has a direct impact on financial performance of the firm. Thus, try to keep your people engaged in challenging work.

- Perspective is important. Your people and yourself might be looking at the same problem from a perspective that doesn’t allow you to get the right information you actually need. Thus, try searching for a different perspective.

- The bar might be too high objectively; or your firm might not be there just yet (resources, skills, discipline) to have a shot at an ambitious attempt. Subjective assumptions about the challenge can also be in the way. An outside observer can help with identifying objective limitations and subjective impediments.

- If you’re in a managerial position help one eager subordinate succeed so that they can “sell” the success story to their peers. Help comes in different shapes and forms. To increase the chances of change adoption approach those who continue to try the hardest. You don’t want your advice to fall on deaf ears. Change will be fueled by people who really want things to change. Everyone else will come up with reasons and creative excuses.

- There are a million things you can change in your attempts; something will work out eventually. To save yourself time and resources, find an external assistance of someone who knows what’s likely to work best for your firm.

- The partner / manager / principal — whoever is responsible for setting goals to the subordinates has to monitor the progress and analyze performance, make amendments and encourage people. When the firm’s leader fails at this someone else will eventually occupy this position informally.

The awezzom question of the day:

What performance benchmarks are relevant to our circumstances?