We seek context to make sense of things. I remember attending a networking event when someone had asked me about my occupation. To which I replied, “I’m a consultant.” A pause. “That’s very broad,” the inquirer responded, “what do you consult on?” Another person standing next to me pitched in, “Which one of the two Bobs are you?”

This was such a witty reference to the two efficiency consultants from the Office Space movie who were hired to “help us run things smoothly around here,” aka, to fire a bunch of people. Basically, and rightly so, the person asked me: “What would you say … you do here?” Of course, I should’ve replied that “I have people skills … What’s wrong with you, people?!”

Buyers of professional services — just like everyone else — want to make sense of whatever novelty they encounter. Saying you’re a lawyer, an accountant, an engineer, a recruiter, a marketing specialist, or a consultant doesn’t provide enough context to comprehend, box, label and ship you to the memory storage for processing.

For better or worse, shortage of information may put you in the same mental category as Ah, those guys — whatever that might mean for the particular buyer. The same principle applies to individual professionals, practice groups, firms, as well as service offerings. Encountering anything new, we all rush to place that unknown entity in a category (loose or tight), draw borders around it, — as if placing it in a box — label it, and place that labeled box into additional context when required.

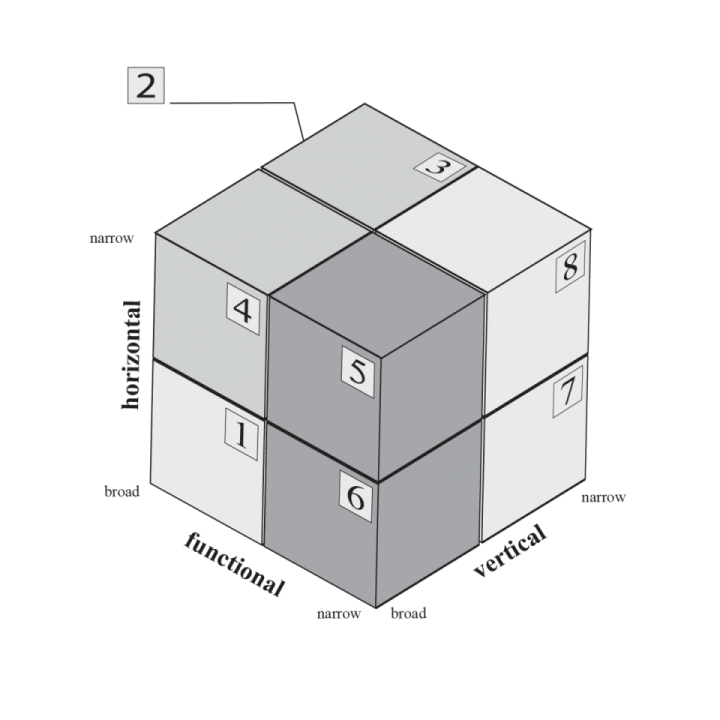

With regard to professional services, what buyers seek to figure out first can be categorized into three primary dimensions: functional markets, vertical markets and horizontal markets. Each dimension has two tails: broad and narrow. Neither is better or worse. The interplay of these primary dimensions defines the Map of Contextual Positioning (MCP); see Figure 1. The position on each dimension isn’t binary in an absolute sense: neither completely broad nor completely narrow.

Also, MCP may be applied at the level of an individual professional, a practice group, and a firm. For the most part, I will be thinking about the firm level, but the following ideas typically apply across the board.

The Functional dimension explains the breadth of service lines of the firm. One professional firm may decide to compete with a very broad range of services, while another may have a very narrow focus. For example, law firm Moreberg & Partners may offer to handle litigation, arbitration, mediation, M&A, IP, and employment matters. While law firm Lessermann & Thatsit may only specialize in intellectual property law. Comparing the two, the latter firm has a narrower functional market position.

The Vertical dimension describes industries and professions that may be interested in the firm’s services. This dimension is often called industry verticals or vertical markets. Most verticals can be found in these two industry classification systems: American NAICS and European NACE. Similarly to the functional dimension, a professional service firm (PSF) may target buyers broadly or focus narrowly. For example, a marketing firm may target buyers from a beverage manufacturing industry (NAICS 3121) broadly while its competitor may focus exclusively on breweries (NAICS 312120). Albeit focusing on the same broad vertical (3121), the two firms have different positioning on this dimension.

The Horizontal dimension describes demographics such as age, family role, income level, job title, team role, company size, and geography. These criteria will be different for B2C versus B2B. Again, a PSF may target buyers broadly or have a narrower focus. A broader horizontal positioning may be (e.g.) small businesses with less than 50 full-time employees (FTE) in the U.S. A much narrower positioning may be: CMOs of Fortune 500 companies.

Each MCP dimension is imbued with trade-offs.

Broad functional

Broader positioning in functional markets significantly expands firm’s capabilities of attending to various client needs. This may seem as a perfect match for buyers convinced of the one-stop shop superiority, for example. Although often executed poorly, cross-selling opportunities are always on the table for broadly positioned firms. Conversely, service offering galore automatically presumes more competition which implies additional price pressure. From the buyer’s perspective, the more service offerings on the menu, the more evidence for the lack of special interest in the one service the buyer wants most.

In addition, to support wide range of services, firms have to either hire more professionals, or breed generalists, or entice functional experts do less specialized work. The latter option is the least favorable, of course, because it’s a high-cost arrangement. And of course, the more diversified the service lines, the more challenging it becomes to efficiently manage the whole mess.

Narrow functional

On the opposite tail, having its upsides, narrow functional positioning has always the risk of becoming too narrow. During major market shifts, the river of plenty may turn shallow or dry out completely.

On the flip side, for the smallest of firms in mature markets without supply-demand imbalance, this may probably be one of the best positions to look at. Because it allows for faster expertise development, and it is always much easier to go broader fast should the demand for deep waters of expertise dry out all of a sudden.

Another benefit of the narrow functional rests with potential subcontracting for firms working on large, complex projects. Referrals among other-discipline providers is another likely opportunity. It’s also somewhat easier to justify higher multiple during M&A negotiations as well.

Narrow vertical

Narrow vertical positioning offers the benefits of building the name recognition in one industry. In addition, because PSFs are primarily in a relationship-based business, rubbing elbows with the same people at the same industry and networking events is a significant competitive advantage. Basically, in five years time your partners will get to know most of the 1,000 (or so) people who attend the same national conferences; and all of them — due to hanging out with one another — will get to know about your firm faster.

The downside to narrow vertical focus are inevitable myopia to developments in adjacent industries as well as risks of tying oneself to a (potentially) sinking ship. Another one is — which is more of a double edge sword — reputational risks. If one of the partners screws up big time, the long shadow will be cast over the entire firm. In a tight vertical positioning news will spread like wildfire. But that is also true for great news, although to a lesser extent because we’re all wired to predominantly be on alert for all things grim.

Broad vertical

Broader vertical positioning, on the other hand, offers variety which can be great for growing junior professionals who haven’t recognized their special interest in a narrow vertical yet. It offers opportunities to explore and diversify. It may also provide a favorable image in the eyes of a multi-industry buyer. Clients that themselves manage a diversified portfolio of businesses may consider a vendor with expertise and experience in several verticals as a more suitable service provider. In addition, exposed to heterogeneous client demand in several industries, professionals can notice emerging common patterns and propose novel service offerings.

Broad horizontal

Broad orientation on the horizontal dimension has an allure of an immense addressable market. Client variety, scalability, economies of scale, and diversification opportunities seem too good to say no to. That is in theory, of course. For PSFs, it’s not that easy to pull off (e.g.) scalability and economies of scale successfully. Professional firms operate differently than manufacturing companies. If a firm isn’t selling productized mass-market services horizontally, it’s selling capacity which always requires additional capital. Such an orientation typically results in intense competition, non-existent client loyalty, and high fungibility.

Narrow horizontal

Narrow horizontal orientation provides the benefits of tailored marketing communications aimed at specific demographics and perhaps psychographics, making it easier to push the right buttons. To identify and reach out to decision makers, tools such as LinkedIn Sales Navigator can be of great use.

The narrower the horizontal focus, the more likely the service provider will understand how people with similar challenges think, act and perceive the world. As a result, service offering customization and targeted messaging becomes much easier. On the other hand, positioned too narrowly in horizontal markets may result in insurmountable challenges with actually meeting the members of the target audience in person. Because they might not have an event or conference to congregate at.

Analyzed closely, you’ll notice that most of the pros and cons of narrow positioning on any one dimension will also apply across the narrow orientation on the other two dimensions. The same applies to broad positioning.

Eight Octants of Contextual Positioning

Because decisions to hire any professional firm to provide specific services are made by people who themselves work in specific contexts — specific job titles at specific companies that operate in specific industries — there is always an interplay between the three primary dimensions. Therefore, such an interconnection may be represented via a three-dimensional model.

Figure 1 exhibits these three dimensions: functional, vertical, and horizontal. Each dimension has two opposite tails: broad and narrow. Each tail impacts the tails of the other two dimensions simultaneously. This creates a 2x2x2 matrix with eight unique octants. In essence, each octant represents a generic positioning strategy based on context alone. This 3D model (that looks like a Rubik’s cube for beginners) is called Map of Contextual Positioning.

Apart from this map, the are two additional maps that provide much nuance to available generic positioning strategies. However, in some scenarios, it is possible to attain real competitive advantage just by Contextual Positioning alone: selecting a market position with low competition and sufficient demand. For example, by recognizing absence of direct competition in an unrecognized niche and going narrow on all three contextual dimensions at once. Because markets continuously change, and broad versus narrow is always a spectrum, the opportunities to identify a new category are never completely exhausted.

Octant 1 represents one of the most straightforward generic positioning strategies. It does not require a lot of sleepless nights to formulate: “We will provide any and all kinds of services requested by anyone who might be remotely interested. We will not say no to nobody. Should we identify a new client need, we will seek to hire whoever is capable to deliver. Work is work. All money is good money.” Essentially, this is a Generalist’s approach.

Octant 8 is the exact opposite of octant 1 strategy: “We will be exceptionally picky about the kind of services we will provide, which industry we’ll focus on, and which clients we will say maybe to.” This represents a Specialist’s approach.

Considering just the Contextual Positioning, the rest of the octants fall on the Generalist-Specialist spectrum. Here are the examples of octant 2 through 7 strategies in a nutshell.

Octant 2: “We work with law firms of all sizes, and try to accommodate all their [blank] needs.”

Octant 3: “We work with CMOs of largest law firms in the U.S., and try to accommodate all their [blank] needs.”

Octant 4: “We work with CMOs of Fortune 500 companies, and try to accommodate all their [blank] needs.”

Octant 5: “We work with CMOs of Fortune 500 companies, and provide a handful of very specific [blank] services.”

Octant 6: “We work with companies of all sizes, and provide a handful of very specific [blank] services.”

Octant 7: “We work with accounting firms of all sizes, and provide a handful of very specific [blank] services.”

It isn’t obvious which of these six market positions is more specialized. Is it octant 2 service provider with narrow industry focus and broad service lines versus octant 6 firm with narrow functional expertise yet broad vertical orientation versus octant 4 vendor narrowly focused on a specific horizontal market?

Consider a client and two vendors. The client is a mid-size epoxy adhesive manufacturer headquartered in the U.S. with a dozen operations abroad that currently seeks tax services to support its international operation. Vendor A — NumberCrunchers Without Borders is an accounting firm that specializes in international tax consulting and serves all sorts of clients — big and small companies from different industries (octant 6). Vendor B — Bean, Count & Export Accounting is another firm that offers all imaginable accounting services (including tax) specifically for building material manufactures of this size that operate internationally (octant 3). All things equal, will the client perceive firm A to be a greater specialist than firm B?

Firm A knows a lot about international tax, therefore, may have an advantage in technical expertise. But does firm A understand the client’s vertical enough to apply its knowledge well? Firm B knows a lot about the client’s industry, but does it have enough experience with international tax? From such an analysis, it’s not that clear which firm is a bigger specialist. And such an analysis occurs quite often when buyers (e.g.) compare both vendor websites.

Therefore, making a claim that narrow positioning in any one dimension makes someone a specialist and everyone else generalists has no basis for an adequate comparison. For that matter, it may be more accurate to suppose that narrow focus on two dimensions coincides with higher specialization. Regardless, given different purchasing scenarios, each service provider may have significant competitive advantage over other-octant vendors. It all boils down to buyer preferences. Who is a specialist and who is not is a judgment call that rests with the buyer’s predisposition toward particular strategy.

More importantly, the question that’s often brushed to the side by PSFs is: Does the buyer want a Specialist on the job? Perhaps, a Generalist is more than enough this time? It isn’t always about who is the most efficient, experienced and with most expertise. Because clearly the most narrowly positioned vendor should always win. But it doesn’t happen. Oftentimes buyers prefer options that are good enough to attain their goals.

Timing dimension

There is an auxiliary dimension that works in conjunction with the three primary ones — timing. Some firms may find success in targeting buyers whose interest in specific services peaks at certain points in time and then evaporates into “We’ll think about it” limbo. For example, all sorts of post M&A assessments, urgent succession planning after unexpected partner departures, sudden opportunity to enter new geographic market through lateral partner hiring, and so on.

This dimension runs from specific to any timing. The latter suggests absent orientation toward time-bound problems, challenges, goals or opportunities. This dimension runs sequentially in serpentine-like path from octant 1 (any) through octant 8 (specific). The more the firm will tend toward a generalist (octant 1), the less important time specificity. The more of a specialist (octant 8) the firm tends to become, the more interest toward specific timing.

In practice, this orientation may be observed when (e.g.) sales managers using LinkedIn signals swiftly react to changes in prospects’ job role transitions, employment status, moving to a new geographical locale, and so on.

The best contextual market positions

A reasonable question follows: which market position is better? Having selected a particular positioning strategy, which service provider will be better off: octant 6 firm or octant 5 firm? Is octant 4 preferable to octant 1? Perhaps, a special combination of the two is a winner? To address this question, we have to define better first.

For some firms better means rapid growth in employee count and revenue. For others, it’s grounded in productivity — higher net fees per FTE. Some firms pursue higher profit margins. Other firms want to improve their bid-to-win ratios. While other PSFs seek to achieve the right balance across many operational gauges striving for a more sustainable business. Different market positions are better fit for different purposes.

Typically, generalists should be able to generate more revenue but will also tend to have lower productivity (measured in net fees per FTE). Because profitability depends on the cost structure, each octant has the potential to be equally profitable (when measured as net profit margin). The better position will always depend on what metric the firm is after.

Another legitimate question may pop up: Is it possible to combine all the benefits from narrow and broad positions in a configuration of a superposition — being in every market position at the same time? To the degree, it is possible. However, this will not occur naturally.

We can imagine (or think of) a large firm or a holding company that isn’t known for anything specific other than bigness. As a firm, they may be perceived as overpriced generalists. Managed exceptionally well, the firm could maintain degrees of specialization of various distinct practice groups. Within and across those practice groups, special opportunities for para, junior, journeyman and senior level professionals could be arranged to offer generalist-specialist spectrum career opportunities. Well thought-through processes and systems will have to be put in place to be able to take a shot at such superpositioning. Much trial and error is required.

Theoretically, it’s doable. Practically, a rare firm can attain and (!) maintain superpositioning. That’s why there won’t be many of those around.

Competition matters

Any professional firm has both direct and indirect competitors. The former strategic group (using Michael Porter’s language) is the one to be most concerned with. Those rivals occupy the same octants on the MCP. In other words, direct competitors have the same market positions. Apart from identifying direct competitors, the MPC model is useful in establishing which vendors aren’t in direct competition, and which ones may be of concern during engagement bidding.

Following the direct competitors, the next strategic groups to be concerned with most are found in the following octant pairs: 1 and 2, 3 and 4, 5 and 6, 7 and 8. For example, if your firm employs an octant 6 positioning strategy, apart from the same-octant firms, the most serious competition should be expected from octant 5 firms.

Octants that are diagonally opposite on two different planes are typically non-competitors. For example, octant 1 and octant 8, octants 2 and 5, octants 3 and 6, as well as octant 4 and 7. If you ever find yourself in an RFP/RFQ process competing against an opposite-octant firm, that should raise a red flag that signifies one of the following.

First, the buyer is completely confused about which strategy is best for their goals. Second, your firm is being played like a fiddle. Third, your firm is a preferred vendor and other firms are being played to either bring the fees down or to get more concessions from your firm. Fourth, you might’ve accidentally entered the wrong beauty contest.

Each market position on this Map suggests a different strategy. When a buyer evaluates service providers across these positions, it estimates (makes assumptions) which vendors’ offerings are a more likely path toward attainment of buyer’s goals. When all goal attaining strategies are good enough for the buyer, they are more likely to choose among octant 1 vendors because they tend to look cheaper.

When all vendors look the same, — and they do when clients have no criteria for selecting the best fit — the next obvious question then becomes about energy consumption. “What will it cost me — the buyer — to employ that strategy over another?” This isn’t just about the money.

From the buyer’s perspective that which is going to take less effort, thinking, and hassle equates to less physical, mental and emotional energy spent. If that means working with broadly positioned vendor B rather than narrowly positioned firm A, so B it.

Note, buyers often specify their goals incorrectly. Nevertheless, this is how decisions are made. “These nice guys work at a large, reputable firm and have such a broad experience. Those other pompous pricks focus just on one area. What if we need something else from them? And we’ll have to wait in line for two months!? Pff... Who do they think they are!? Screw them. Let’s go with those nice fellas from that large (safe, available, convenient) firm. Come to think of it, we don’t really need an expert specialist, do we?”

Selecting Contextual Positioning, — adjusting the sliders on all three dimensions — the firm is inadvertently choosing the number of prospects and often, as a result, the number of potential competitors. It isn’t always the case, but typically the narrower you go the less competition and less buyers there are.

Going narrow in all three dimensions simultaneously allows for much quicker expertise build up and potentially higher fees. However, it’s also typically a growth limiting factor. The narrower you go, the less prospects there are.

On the other hand, going broad on all three dimensions by accepting all sorts of work from all kinds of clients at fixed lower-than-market-average fees may allow a PSF to grow much faster than the bulk of the market. The latter is a typical strategy of many professional upstarts. Due to inherent low margins, not everyone is capable of pulling it off long-term, especially when market demand begins to decline and price pressures increase.

One might argue that a better market position is the one with the right amount of competition: not too small, not too big, ju-u-u-ust right. However, it’s not the volume of competition you should be concerned with (although it’s often a strong signal of existing demand), it’s the ability to create and maintain competitive advantage over competition.

When it’s shaky, there are two additional maps at your disposal. They too offer generic strategies complementary to the ones described by the Map of Contextual Positioning.

If you’re interested to learn more, subscribe and get notified when I publish information on additional material.

The awezzom question of the day:

What’s our current and preferred contextual positioning?